Food for economic development: building regenerative food systems

Notes from Cali, Colombia : Part 1

I was delighted to have the opportunity to spend the last few weeks in Colombia.

I could wax lyrical about how amazing Cali was… the food, the salsa, the hospitality. But I won’t, because other people’s holiday stories are annoying.

Preparing for my keynote, the assigned topic was, ‘food as a tool for economic development.’ It forced me to think about:

What do I mean when I advocate for food as an essential tool in combating the climate crisis?

When I say that empowering active food citizens will help reconnect people to the land and their environments?

When I discuss the development of regenerative, regional food systems in conversations about post-covid economic build-back or job creation for young people?

After the rollercoaster of the last three years, it was time to take a pausa, sit in a hammock and figure out what I’m trying to say about food.

With permission from the Delice Network, I’ve edited and published my keynote below. It’s split across two emails because it’s long. The first focuses on learnings from my career to date. The second makes the case for regenerative, regional food economies, looks at examples of existing projects and implores you to stop saying the earth is doomed.

Introduction

Thank you for having me

Been in Cali for a week already, and we’ve had the most phenomenal time.

From Martha’s Restaurant to bird-watching at a Finca in the mountains, it’s been a privilege to experience the culture, food and people of this place.

For many of us, this conference represents the first opportunity to be physically together, travelling to exchange ideas and information, since before Covid.

I don’t know about you, but I’m not the same person I was three years ago. We have all grown and been changed, suffered and witnessed the suffering of others. We live in a time of great, global uncertainty. A time when it’s easy to feel despair at the state of things…

So, I invite you to suspend your ideas about everything wrong. Instead, we’re going to focus on what’s possible, explore what we have learned, and discuss how each of us can help build a fairer, more equitable planet, through the lens of developing food economies.

If you take away nothing else from today, I ask that you leave considering the following:

o How can we be in the business of building cultures of good food as a tool for economic development?

o What can be achieved if we put a collaborative, cross-sector approach at the heart of regenerative, regional food economies?

My Story

When I meet people these days, I have a practice of introducing myself with the story of who I am - a way of setting the tone for future relationships.

As Martha said, when I met her earlier this week, ‘I am a radical and emotional woman.’ I have decided to start unapologetically introducing myself as such because the times we are living through demand it of me. Because if I can find the courage to introduce myself this way, I hope it will permit those of you here to also occupy a space of radical, emotional commitment to the topic we’re discussing… even if only for a little while.

My name is Aine Morris. I am 39 years old. The firstborn daughter of an Irish immigrant mother, and a father from Lancashire in the North of England. My childhood was not an easy one. My father was a violent man. I was 16 when I left home, and 21 when I had my daughter, which is where my food story begins.

Having a child at 21 was a challenging experience, but it also changed my life for the better. I had responsibility for this tiny baby and more than anything, I cared desperately about how I was going to feed her.

It was because of her that I grew interested in organic food and food education. Eventually becoming involved with Slow Food and discovering the ‘The University of Gastronomic Sciences.’

Why am I telling you this? Why does my story matter? It matters because I was a young person whose life was transformed by food, and we have a lot of young people in the room here today. Share about the UNISG scholarship programme and invite them to visit the University website.

Slow food changed my life

Gave me people and community

Showed me the power of story, conviviality and the importance of food as a tool for change.

While at University, I was founding coordinator of the Slow Food Youth Network - a project developed by UNISG students to encourage young people to engage with the Slow Food movement in more dynamic and political ways.

We organised the youth delegation at the bi-annual ‘Terra Madre conference. We developed initiatives such as ‘Eat-In’ and Disco Soup. We encouraged new youth members and brought a fresh perspective to an organisation sometimes dominated by wealthier, older eaters. International Disco Soup Day happened while we’ve been here in Cali, and Martha has been excited to share the activities of Latin American youth. It’s inspiring to realise that a project seeded at a faraway University over 10 years ago, still lives on through the activities of young people in Colombia today.

I left Slow Food with the understanding that food could transform lives. And that food people were a powerful dispersed network, existing all over the world, which when brought together and made visible, could be a significant force for positive change.

What I learnt from my time in Italy was:

Non-hierarchical structures will be key in the future. The existing top-down approach to business and governance is going to shift significantly. Communities will be forced to become more self-reliant as a result of the climate crisis. Cities and regions can support the necessary changes by building infrastructure that enables new kinds of food communities to thrive.

There is power in physically bringing people from different backgrounds and cultures together, to share knowledge and exchange ideas. Dispersed networks are more self-reliant, and often less joined-up. A healthy food system, like any system in nature, should be complex and biodiverse. Connection and integration will be key. Replicating biodiverse, natural systems is a food security strength. In-person meet-ups allow for community building, inspiration and exchange of best practices.

Story is everything. More on this later.

Sustainable Food Trust

After University, I moved to Bristol in the South West of England, where I was Head of Communications for the Sustainable Food Trust – an organisation that focused on high-level interventions with those ‘in a position to influence maximum change.’

During my time here, I produced the 2013 ‘True Cost of Food’ conference and worked on programmes that aimed to get policymakers looking at how we might account for the environmental and public health externalities of different types of food and farming systems.

What I learnt from my time at SFT was: the cultural shift required to tackle the climate crisis is not going to come from those that have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Those that have significantly benefited from existing systems of finance and production will not be the people responsible for overseeing change at the speed and scale required to limit 1.5 degrees of global warming.

If we’re going to deal with the converging challenges of climate breakdown, Covid, and food security, (and in my country, Brexit) it will require a critical mass of citizens, actively engaged in the production, processing and community consumption of food.

The shift that we need is cultural and psychological. It will only come from empowered food communities, built by actively engaged citizens. It will not come from existing structures of power and influence.

Abergavenny Food Festival

In 2015, I took a sideways leap away from sustainable agriculture and wealthy land-owners, back into the world of festivals. My experiences organising for Slow Food, meant I’d seen first-hand how transformative events could be, as a tool for driving alternative thinking and behaviour change.

If the right balance of engaging and educational content, could be added to the joy, possibility and community you feel at a festival, then maybe (just maybe!) we could open minds, change perspectives and leave people thinking differently about how they eat.

Could a food event be a vehicle for engaging the public in co-creating the food system we need?

Could we be in the business of encouraging a public passion for rebuilding local food cultures?

Was experiential community engagement the key to building not only the system but demand for that system?

Side point: We spend billions of pounds a year globally on programmes related to diet, nutrition, health and food policy, but if the public is continually driven to purchase food from major retailers at the cheapest possible point of consumption, we can promote all the healthy/local/ethical/sustainable alternatives we like... we’re not going to achieve sufficient critical mass to cause a shift to the global market.

I spent three and a half years as Chief Executive of the Abergavenny Food Festival. We delivered a 3-day event each September, which welcomed more than 40,000 visitors to a small Welsh town, just outside of Bristol.

So, was it successful? Did achieve what we set out to do?

Lots of positives, but also immense challenges. It is almost impossible, in the UK, to separate issues of class, wealth and privilege from the restaurant and hospitality industry. Did we make a difference? Did guests leave thinking differently about how they ate? Or did we throw a fantastically good party with £10 cocktails and £12 lobster rolls?

Conclusions:

The ethics and principles of running a successful event is a much bigger topic for a different day

Yes: there is a case to be made for food events that network farmers, chefs and producers, develop public demand in the marketplace, and engage, educate or promote ethical food to the public.

BUT: this in-and-of-itself isn’t enough. Making a long-term difference to local communities requires resourcing and commitment to a year-round programme of engagement and inclusion. Events must be sufficiently resourced to deliver positive experiences internally, as well as externally.

No: food festivals that support the idea of ‘foodie’ entertainment as a leisure activity are a big part of the problem. Most events are naturally human/waste/resource intensive. You have to be delivering a lot of good stuff to justify their existence.

Side point: The UK (might be less of an issue in other countries) is unwittingly operating a two-tier food system. Covid highlighted that a significant percentage of our best food producers – local, ethical, heritage products – are almost exclusively selling into the UK restaurant and hospitality supply chain.

When Covid hit, these smaller, independently-owned producers were the ones in financial trouble the fastest.

The situation highlighted how the majority of consumers still eat, almost exclusively, from the global, industrial supply chain. While our ‘food movement,’ ‘artisan’ or ‘craft’ food producers are almost exclusively retailing to those who can afford a ‘foodie’ alternative. This is a food security issue. It leaves those producers at significant risk from future shocks.

The situation also highlighted the essential role of chefs as custodians of our national food heritage – chefs value and purchase these products, and keep putting them on menus. UK hospitality is acting as custodian of certain food and drink products by educating and advocating for a market that a) wants to buy them, and b) can afford to eat them.

This is both a delight to understand – there is an opportunity in developing the role of chefs as cultural custodians – but also a risk to the food-producing community. What if another pandemic hits? What if the industry can no longer afford your products? What about all those who can’t afford to buy the most food-secure, regional foods? How do we create broader demand and access?

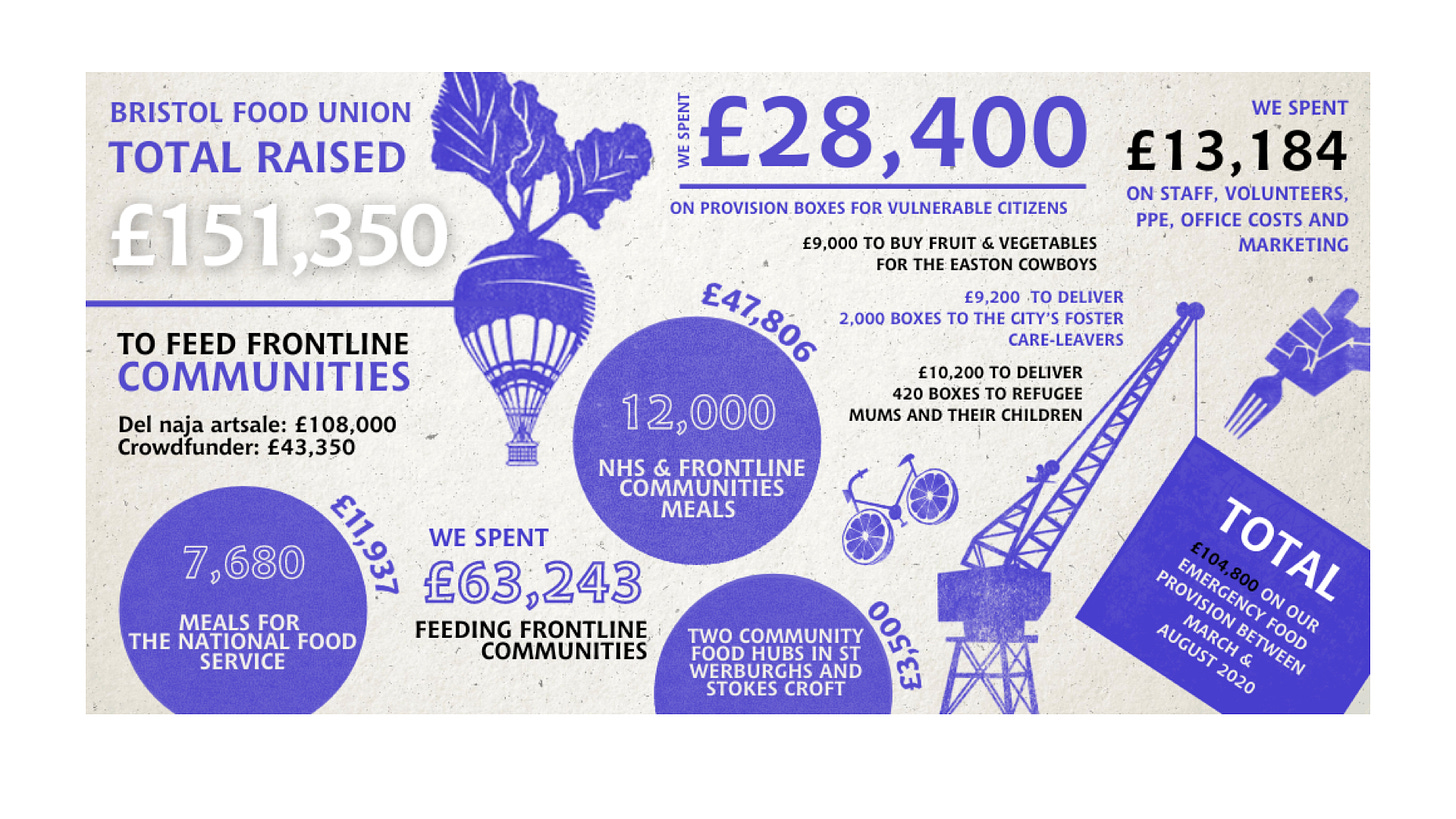

Bristol Food Union

What happened in Bristol when the pandemic hit?

72 hours from meeting to crowdfunding, brand identity and press release. Tell a great story. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you need.

How did we achieve ask and reach so quickly?

o Existing media relationships

o Massive Attack support

o Joint social media reach: aligned messaging and tone across multiple hospitality channels

o Empowering comms – ‘Buy One, Give One.’ ‘Help us to help them.’ ‘Help from the safety of your own home.’

The Ask:

Money from the public – pay chefs to stay in kitchens - get food to people who needed it. Clear, simple, direct.

Shop Bristol Food: everyone played their part. Bristol Food Producers created a database. Web design, social agency and comms support were also essential. Not just restaurants and kitchens, but also those who knew how to design and run a strong citizen engagement campaign from a communication and fundraising point of view.

Foster care boxes: commissioned by Bristol City Council. In Bristol, our corporate childcare department cared about supporting the city’s young people. Not necessarily the same in every region. Expand.

Refugee/asylum-seeking communities: we reached people that weren’t otherwise supported by existing provision. Spot the gaps. Meet the need the community asks for. Not what you think they want or need.

Food jobs Friday: supporting the industry as the crisis evolved. Be willing and ready to adapt your offering as the situation changes. Careers in food continue to be a significant issue in the UK - an industry-wide action plan is needed (one that straddles both hospitality and farming/food production), creating opportunities for integration and connection across both industries. We should also undertake a national review of our farming and hospitality training pathways, updating them to meet the needs of a rapidly shifting industry and climate.

Lobbying politicians: We added our voice to the national calls for industry support. Relayed information, was then presented in Parliament. At present, food and agriculture lobby in silos. Hospitality, farming (sustainable and conventional), and the food industry all advocate separately. UK food and hospitality, farming and environmental/climate organisations would benefit from collaborating on strategic ways to lobby as a joined-up whole.

Disseminating information to restaurants: grants, furlough, insurance, funding, advice. Boring, but someone needed to do it. Helpful for the council and authorities to have a direct line of communication with the whole industry.

Conclusions

Bristol Food Union evidenced the need for trade groups or restaurant associations. Representative organisations can play a strategic role in disseminating information, aligning businesses behind joined-up communications and identifying opportunities for collaboration, media engagement, group buying or industry development.

Nutrition and quality mattered. Home-cooked meals mattered. Not just supply chain waste. Individual assessments for users. We made enquiries about access to cooking facilities and cold storage. Tailored support that gave comfort, dignity and more than.. to people in need. Touch briefly on Fareshare issue.

Sustainability and resourcing over time was a significant issue.

What was achieved in the first 12 months?

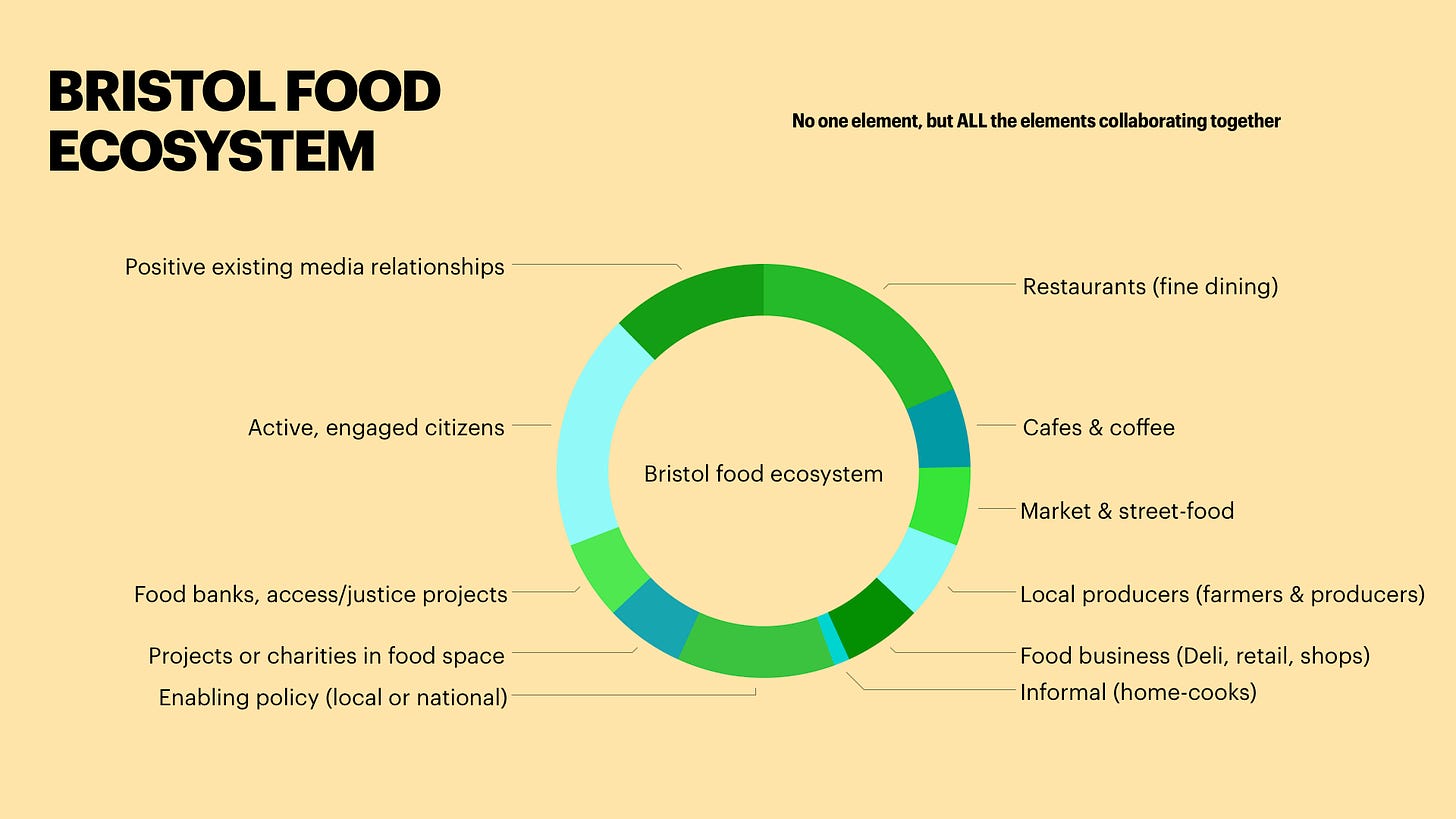

Bristol’s existing food ecosystem

So, how were we able to do what we did in Bristol?

How did we deliver a collaborative, cross-sector, city-wide approach that engaged local citizens, met a need and supported the economic survival of an industry?

…. Part 2 to follow.