Food for economic development: building regenerative food systems

Notes from Cali, Colombia: Part 2

So, how were we able to achieve what we did in Bristol?

How did we deliver a cross-sector approach, which engaged local citizens, met a need and supported the economic survival of an industry?

o Because a lot of the work (both formally and informally) had already been done.

See graphic: Bristol’s existing food ecosystem:

No single element, but all these elements working collaboratively

Existing food policy: 2020 Going for Gold. Bristol Food Network: policy and mapping

Existing community of food access and justice organisations: Feeding Bristol, Children’s kitchen etc. Established network and strong direct line of communication with council and Bristol mayor’s office.

Enabling council: direct and effective communications. Support with human and financial resources. One City Strategy - groundwork in place.

Access to resources: public, high net worth individuals, grant funders, council and others, mobilised to make small amounts of funding available quickly, reducing administrative red tape.

Active and engaged citizens - want to make a difference. Social and media outreach to communicate with them.

Well-networked food community (even if informally, across hospitality and food business sectors)

Breadth and depth: The existing ecosystem of different types of food projects and businesses here were diverse. It meant we could mobile across communities, for a more inclusive, city-wide reach. It wasn’t just one Michelin-starred restaurant, but everyone, from the food banks to community food projects, to cafès, restaurants and eateries. We had a strong charitable sector that was missing food. We created varied opportunities for participation across industries, businesses and individuals.

The importance of strategic communications: A strong city food ecosystem should be a diverse collection of all types of food businesses and projects. Like any decentralised network, that is its strength, but also its challenge, because each business or project communicates in its own way. Aligning messaging behind a strategic tone and key phrases, meant we engaged a broader demographic of citizens (those giving, but also those needing support and access.)

The citizen engagement piece is so often overlooked: We spend billions of pounds each year writing strategies or programmes of nutritional change, but very little on engaging citizens in what it means to co-create regenerative, local food communities. Engaging widespread public support for a regenerative national food agenda is an essential missing piece of the puzzle. Whether through communications campaigns, school education, community cooking or events – we cannot successfully encourage the public to eat differently, if we’re not engaged with the work of safeguarding, maintaining and rebuilding our existing food cultures.

Food is a participative, community-led activity. We need to be connecting with the public on how they can participate in the production, shopping, cooking and distribution of food at the community level. Not simply in lower-income communities, which are being told to ‘learn to shop, cook and budget’ by politicians in the UK. But across every background and demographic that makes up our society. Just because you can afford to shop at Waitrose, doesn’t mean you’re not a part of the problem.

In my country, we have already lost a huge amount of the intangible/in-built community systems for exchanging knowledge and information about food. Speaking to all the Latin American, African and other global economies represented here, I wanted to say;

It is much harder to rebuild cultural systems of culinary heritage and traditional knowledge once they have been lost, than it is to safeguard them before they disappear.

Much of what we’ve discussed over these last days about the role of women, as keepers of food knowledge and culinary heritage or the needs of market traders, home cooks and the informal food-producing economy - in my country we have already lost or dismantled, so much of this community infrastructure. Building cultural systems back from scratch is twice as hard as saving them before they’re gone. You have the opportunity to protect your existing culinary cultures. They are hugely important cultural assets. I encourage you to learn from our mistakes.

The importance of existing associations

Representative organisations already existed across various food sectors. When the pandemic hit and citywide reach was needed, these organisations were in a position to act.

Each association on this slide represents a different element of the good food economy.

We had a strong food policy organisation, a food justice and access organisation, someone representing farmers and food producers, and the Food Union emerged to represent restaurants and hospitality businesses. The existence of an association in each area created a broader reach across sectors and locations than we might have had otherwise.

The key things that we saw bubbled up, and the things that really mattered to people in the early days of the pandemic were:

Family

Community (inc. housing)

Food

I make the effort to remind myself of this now. Radical hope and optimism, as a sustainable business strategy. I hold onto a relentless, even earnest belief in society’s power to change, in spite of all the current evidence to the contrary.

Now that disruption is embedded for the longer term, and many people are struggling with burnout and grief fatigue, I find it helpful to remind myself that in the very early days of the pandemic when there was a lot of fear and uncertainty, the majority leaned-in to the positive things that matter most. We naturally self-organise towards love, inclusion and community… if given the chance.

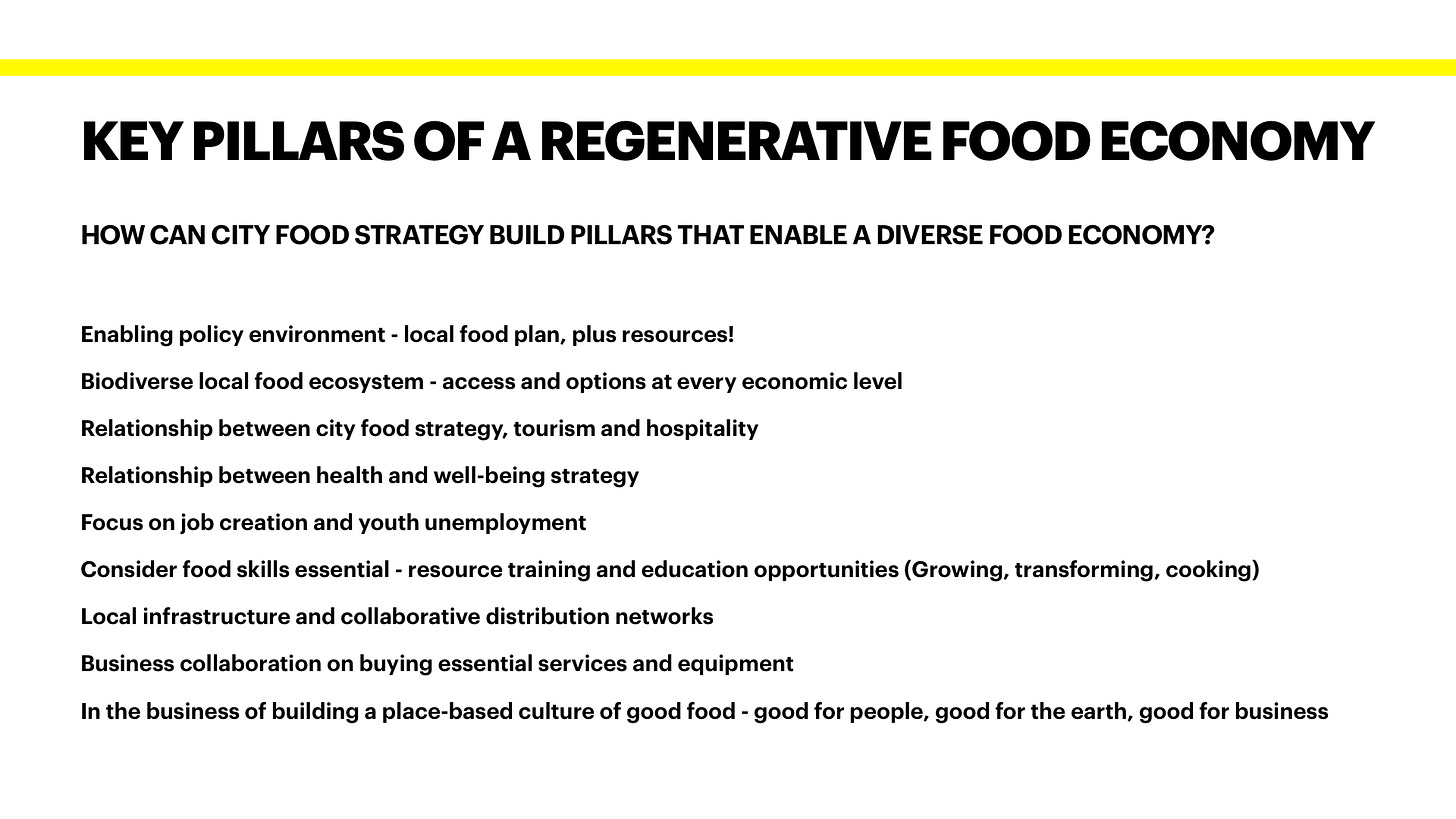

So, what next? And what can we learn from the experiences of Bristol that we’ve discussed so far?

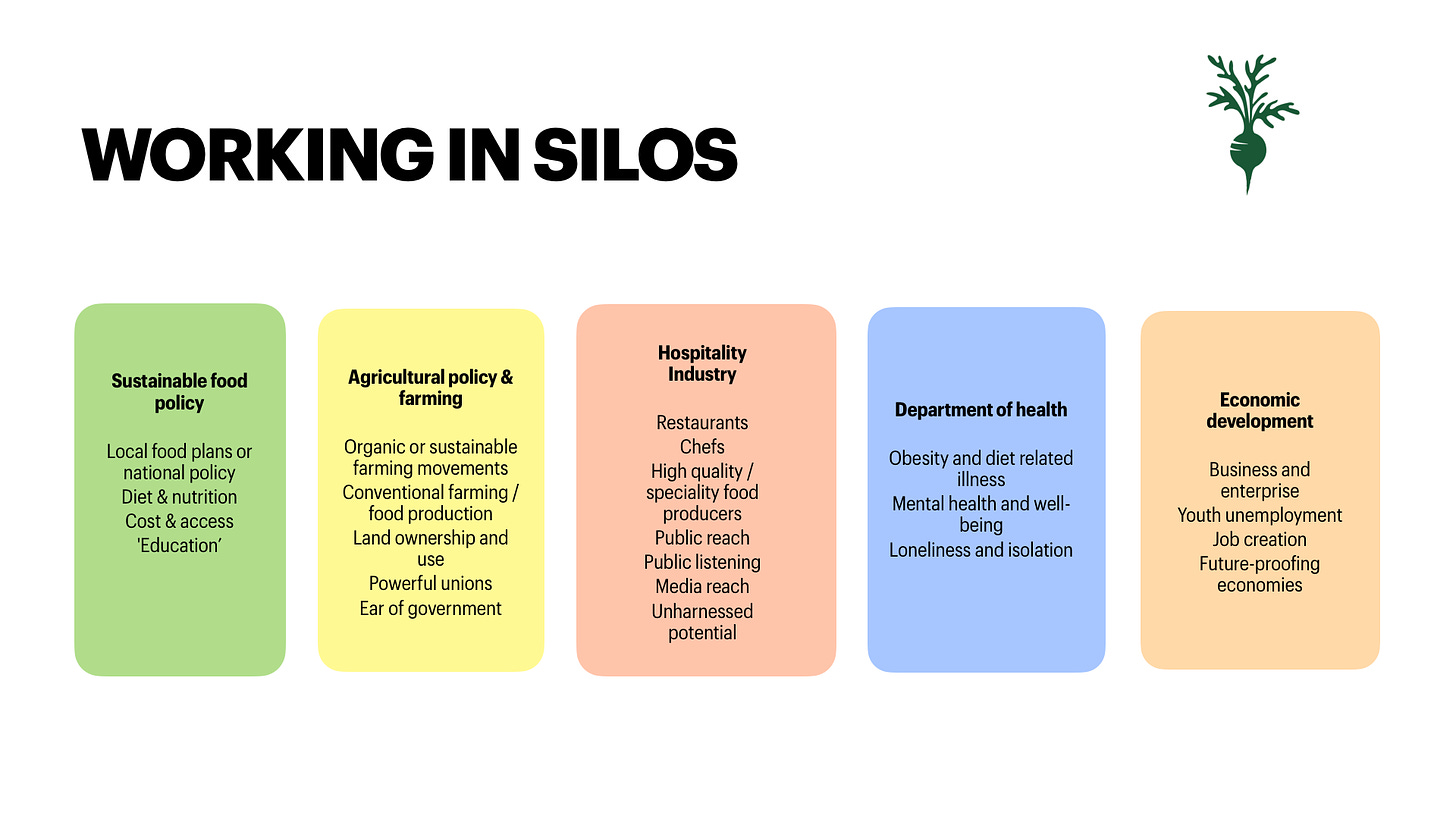

We are still working in silos.

So often we take a reductionist, rather than intersectional, approach to food or food systems change. We consider food tourism as separate from food systems issues, agriculture as separate from work on diet-related diseases.

Real change, looks like integration and mutual objectives being achieved across the sectors described. It looks like councils and city organisations finding long-term opportunities to achieve shared goals, in the more organic, collaborative way they were at the beginning of the pandemic.

The climate crisis means there is little time left for siloed working. Food work needs to be considered (and funded) as a holistic whole. Change in farming and agricultural systems should be tied to rural development and youth enterprise objectives, which could in turn be connected to how urban communities engage with local food systems, which in turn delivers diet and well-being outcomes, or loneliness and isolation benefits for citizens.

Putting regenerative local food cultures at the heart of individual communities, can successfully deliver a whole range of health, social mobility, financial and job creation outcomes. However, most cities or regions do not currently take this intersectional or cultural approach to food systems development.

Speaking with Stephanie Doglioni yesterday (Cali, Secretary for Tourism), she mentioned the civil unrest here in April, as a motivating factor for departments working more collaboratively to solve these problems. Reductionist thinking and fear of complexity is a huge problem in the world. Nature, by it’s very nature (ho ho), is diverse, complex and interconnected.

How can we replicate (biomimic) the organising principles of natural ecosystems to design community-led, regenerative food economies?

How do we build the infrastructure and space for food communities to flourish, in ways they might not have done before the pandemic?

We stand at a unique moment in history. These next 5-years will make or break us. Covid is not a short term health pandemic, it is the first significant wave of the incoming climate crisis. Nothing that western governments are doing, that my government is doing, has instilled me with faith that we are going to make the necessary changes in the time available… so responsibility to take action falls to each of us, at a local or regional level. We require a regional focus. Each of us should be asking, what action can be taken at the city or regional level to ensure that we are capable of feeding our citizens in the event of another health or climate emergency? From a food security perspective, would we be able to feed local citizens with basic staples if we needed to?

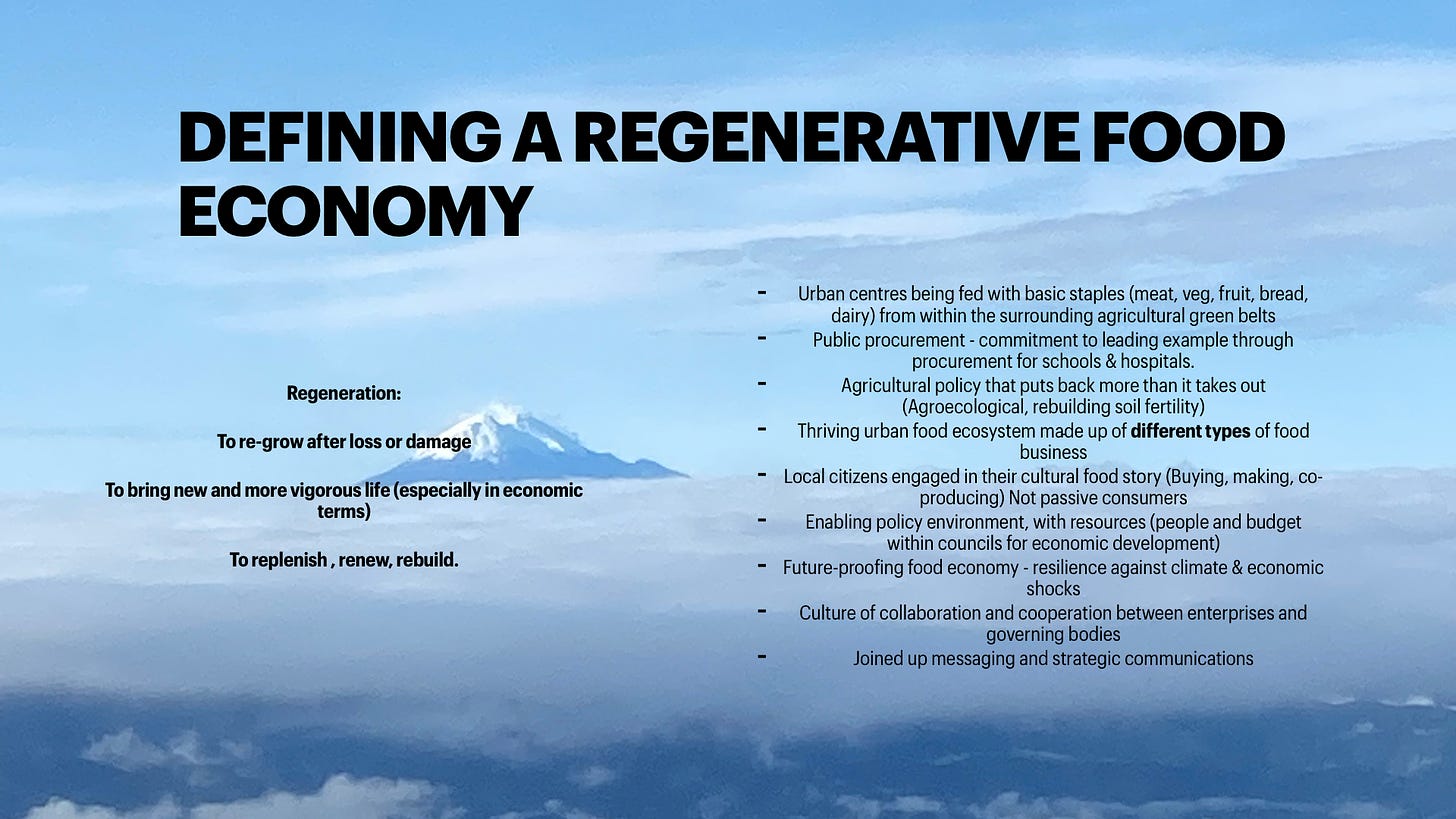

What does a truly inclusive, regenerative food economy look like? And what opportunity does it provide for us to view economic development from a new perspective?

The world ‘sustainability’ has been go-opted. It has been used so widely that it no longer means anything. I prefer ‘regenerative.’ Regeneration is in keeping with the ability of natural systems to grow back from almost anything - a stump, a root, a nubbin. If you’re barely alive, you’re not dead. I’m a great believer in a come-back.

Review points from the slide.

Global examples of innovation

Are there any particular examples of projects or initiatives that are taking this joined-up and cultural approach to driving change around food?

SFYN Disco-soup: engages young people, meets them on their terms, creates spaces for them to care about food and collaborates on projects that inspire them. Youth driven.

Festivals and meat: Northside festival in Denmark & Shambala festival in the UK. Radical meat reduction policy and strong sustainability reporting. Fear of economic cost. Strong public communications are needed. Proper sustainability reporting is an investment. You have to be willing to grow and change depending on the reports, but consumers now are so loyal to these brands.

Gastromotiva : Brazilian project from David hertz – takes young people from challenging economic backgrounds, and teaches cooking skills and careers in hospitality. Lifts youth out of poverty through food – started in 2006, over 100,00 people supported, over 100,000 tonnes of food waste used to date. Food education at scale will be essential.

Zero waste restaurants e.g. Silo in London or SPILL in Malmo – closing systems, driving innovation, reducing food costs. Where food waste comes from, if used as a primary ingredient, is key. How to create close systems of waste in professional kitchens, requires a lot of thought and integrity. It is not the cheap choice. How do we make the case for business models that essentially deliver less profit in exchange for community and environmental benefit? Programmes of grants to support the development of these sorts of enterprises are beneficial. They often initially make a loss in the short to mid-term… How to justify running the kind of business we need for the future, if it’s not economically competitive under our current systems for measuring success? Measurable’s need to change.

Food for Soul: Project of ‘refettorio’ from 3* Italian chef, Massimo Bottura. Inspiring change through food, beauty, hospitality and care. Michelin quality chefs, working with food faste to produce meals, to be eaten convivially in beautiful locations. Consideration of art, ceramics, design etc. Delivering hospitality culture to those living on the streets - is important and significant. Makes a tangible, emotional difference. However, not enough in and of itself. Must be supported with access to social welfare services, counselling and longer-term support.

It’s all about the story.

Like I said earlier… story is everything.

I’m a storyteller by nature.

All of my work involves thinking about how we can tell a story of change so powerful that it helps to reconnect people to the land, their environments and communities.

We live in a world dominated by story. Just like the oral story-telling cultures of old, social media is creating space for every individual story to be seen. This is both a powerful tool for change, and an incredible challenge. Just like the oral systems of story-telling, facts become a more subjective concept. The old ways enjoy a raucous tale, salacious gossip that spreads; values a good story over the truth.

So how can we harness this opportunity? How do we tell a story of our individual food cultures, regions or heritage in a way that drives reconnection to the environment, and creates commitment for safeguarding our collective cultural goods?

People are searching for meaning and community

Powerful stories of hope and change are the ones that will rise to the top.

Authenticity matters

If you don’t walk the walk you risk being called out

There are some examples of innovative food policy work being done at national level, but each comes with their own challenges.

Bhutan: committed to 100% organic agriculture in 2016, but a 2018 report says yields fell by 24%. Country has become more reliant on external imports as a result. How do we account for a global system of conventional agriculture, which artificially inflates yields and deflates costs due to dependency on external (petrol-based) inputs? There will need to be transitionary programmes of subsidy and support to enable our farming communities to transition.

French agroecology bill: 2014, cross-party support – law for the future of agriculture, food and the forest. Applies principles of agroecology to 200,000 small farms by 2025 – training future farmers differently – but 40% of the current farming population is near retirement.. many new farmers will be needed. Interestingly, brings public concerns into account, such as pesticide use. So pesticide reduction in agriculture becomes a public health issue, not just an agricultural systems issue. Also considers health impacts on the most vulnerable, as well as retailer/supplier relations. Independent watchdog empowered to intervene if retailers are not supporting farmers and food producers. However, implementation is a problem! Requires time, resources and a strategic drive to engage a whole new generation of farmers. Agricultural universities and learning establishments rarely get much attention. In the UK, our leading agricultural college has very little serious focus on delivering anything ‘alternative’ or ‘agroecological.’

Copenhagen public procurement: organic, local sourcing policy. A commitment of 4 million euros a year to support the development of local public procurement. 88% of the 80,000 meals served each day are organic. Aiming for 90% organic procurement across all state food institutions - schools, hospitals, and care homes. Organic conversion of roughly 900 kitchens – have spent 6 million euro on training and education. Yearly procurement budget of 40.3 million euros. Copenhagen is a really interesting case study from food culture and development perspective:

One restaurant and a few key people influenced the whole city's commitment to good food policy. Has both strengths and weaknesses.

Much stronger organic farming movement than in the UK. A general acceptance of the health benefits of organic production.

Copenhagen is less developed around social inclusion, supporting refugee communities and community/food access projects, compared to say, Bristol or San Francisco.

We are living through the Story Wars. Whoever controls the story wins. Right now, a story of scarcity, fear, decline and collapse dominates our media and social narratives. There is a huge cost to us because of this. Decline and collapse becomes the self-fulfilling prophecy. People are in fright or flight, which prevents them from feeling empowered to take action.

We need to be in the business of telling a story of radical hope and possibility. A fairytale, if you like, about the potential of people to come together and reconnect with their role as custodians of their lands and communities. Can we tell a tale of how humans came together to re-wild, restore and replenish the planet?

Food is essential. It creates a radical opportunity for change. As Petrini always used to say, ‘everybody must eat.’ We all need to be nourished by food everyday. Whether you’re living in poverty, or you’re the Sultan of Brunai, we all need access to safe, nutritious, affordable food for ourselves and our families.

Food is tangible (unlike carbon): We know carbon exists. We know we need to get it out of the atmosphere and sequester it into the ground, but most of us don’t really understand how – it is a concept, not a physical reality. We can’t taste, smell or see carbon.

But food, food has a direct physiological impact on our taste, memory, feelings and bodies. It can disrupt our perception and recall our fondest memories. It is entirely subjective to every individual’s history and life experiences. Your parents, your culture, your background, your religion, your social-economic upbringing; all have had a direct impact on how you experience food.

Food is personal and emotional. So many of our programmes of diet and nutrition assume we make rational, scientific choices when it comes to deciding what foods to eat. This approach (and all the millions of pounds we spend on programmes that take this approach) fundamentally misunderstand the psychology of human behaviour change. We don’t make evidence-based, rational choices about what we eat. (Most of us anyway!) We make emotional and impulsive choices about consumption.

Change food and we change everything

Change food and we transform individual and community health and well-being.

Change food and we rebuild localised cross-demographic communities.

Change food to empower conscious citizens actively participating in the maintenance and development of their communities, rather than passive consumers buying whatever products the global economy best markets to them.

People connected to the land, seasons, health and people of their place, will actively work to maintain and protect the communities they are a part of.

For me, food is the tool through which we can communicate the changes we need in real, as opposed to conceptual terms. Food is a unique tool that we have at our disposal to rebuild our communities, re-engage citizens, and begin developing the kind of regenerative economies we need if we are to survive the future.

So, I leave you with these final thoughts…

What opportunities exist post-pandemic, for the development of a more holistic, cross-sector approach to food? One that delivers benefits for economic development, job creation, tourism and cultural recovery AND successfully meets carbon, climate change and health-related outputs?

How do we tell a story so powerful that it helps reconnect people to their environment? How do we empower every individual (regardless of social-economic background) to be an agent for the change that is needed? What does it mean to develop active food citizenship?

We live in a time where I feel a deep responsibility to offer people a narrative of hope and possibility – a story about how people successfully came together to rebalance and regenerate the earth. How we found ways to work together globally, to heal from the last 500 years of Western imperialist colonialism and the mass environmental degradation that came with it.

As my mentor, Dr Martin Shaw would say:

For God’s Sake, stop saying the earth is doomed! You may be doomed. I may be doomed. The structure of our environment and societies as we’ve known them for the last 500 years could well be on their way out…

The earth however? She’ll be just fine.

The question we should be considering is… are we happy to be the generations who presided over the collapse of life as we know it, simply because we became stuck in a story of fear, designed to make us deeply resistant to growing in the ever-evolving way that our planetary systems demand of us?

Áine Morris

Cali, Colombia. May 2022.